When it comes to the UK court system, it can be hard to keep track of which courts address which matters, and how they relate to one another. Read on for a full rundown of the legal system – including its hierarchy.

The two types of Court

There are essentially two main categories of courts in the UK – criminal and civil.

- Criminal courts deal with defendants who are accused of committing criminal offences. In criminal courts, the judge must listen to the prosecution/defence and decide, on the evidence presented, whether the defendant is guilty or innocent. The burden of proving guilt is on the prosecution, and they must prove it beyond reasonable doubt. If the defendant is guilty, then the judge must decide the appropriate punishment in accordance with the law – this is referred to as the judge being an arbiter of law.

- Civil courts deal with private disputes, be that contract, commercial, family law etc. The judge must decide, on the evidence, in favour of either the claimant or the defendant. The burden of proving the case rests on the claimant, who must prove their case on the balance of probabilities, meaning more probable than not. Because liberty is not at stake, the standard of proof is much lower than that required in criminal cases. If the claimant is successful, the judge will award an appropriate remedy such as damages (financial compensation) or some other form of order, such as an injunction.

Whilst there are also Appellate Courts, which deal with appeals and sit above all other types of court, and Miscellaneous Courts which deal with other distinct functions, in this article we will focus on the two most common categories above.

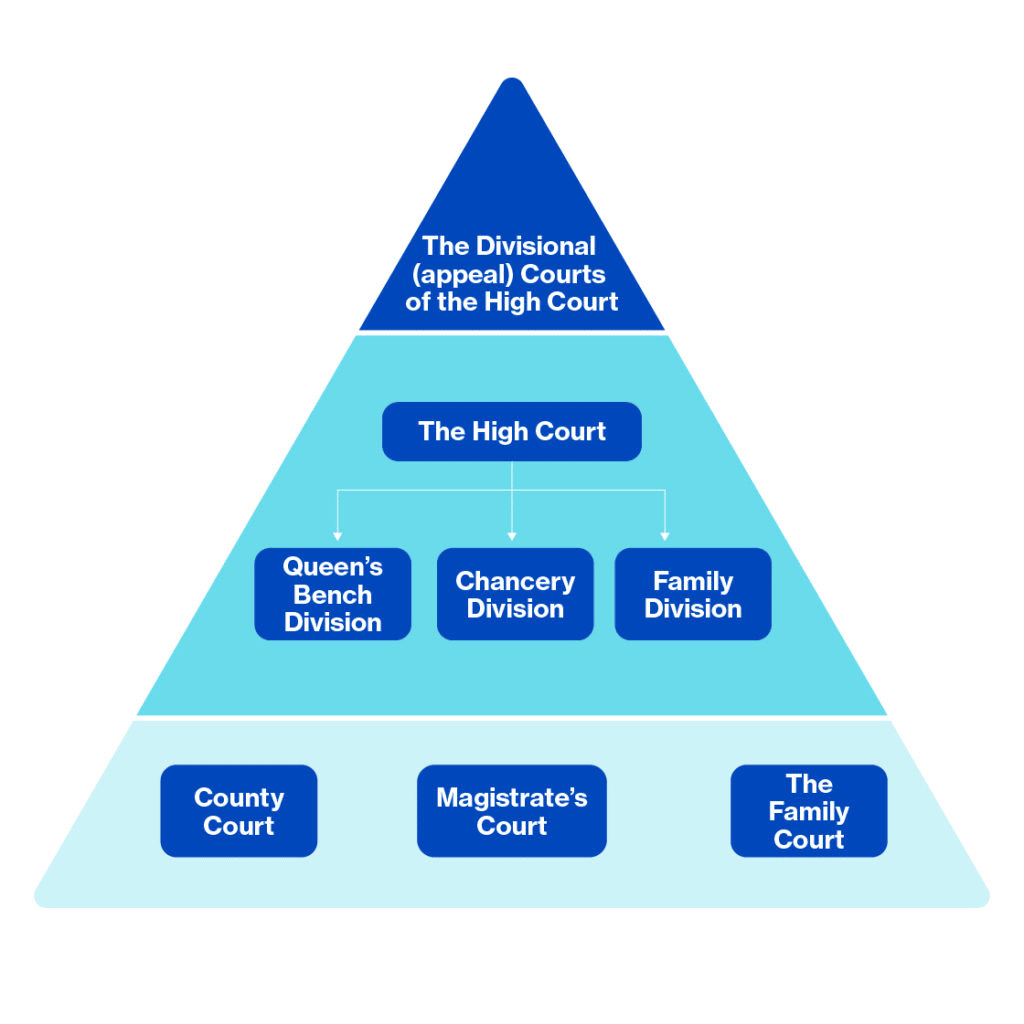

Civil Courts

1. County Court

Most civil cases start life in the County Court. The County Court deals with the less serious civil matters, such as small claims for compensation, breach of contract, minor land disputes etc. Procedure in the County Court is governed by the Civil Procedure Rules, an ongoing body of rules that is continually updated.

2. Magistrates’ Court

Although predominantly a criminal court, Magistrates’ Courts do have power to hear certain types of civil matters, such as licensing matters, and non-payment of bills. You can find out more about Magistrates here.

3. The Family Court

Prior to 2014, family proceedings were dealt with in either the Magistrates’ or the County Court. However, as part of the Crime and Courts Act 2013, the Family Court was created to deal with such matters. Cases such as divorce and domestic violence are covered by this court, but in addition, there are two categories of proceedings relating to children which fall within its jurisdiction. These categories are private law proceedings, such as disputes about arrangements for custody, and public law proceedings, where local authorities bring proceedings, for example, care proceedings.

4. The High Court

The High Court is composed of three divisions, each dealing with a different area of law:

a. Queen’s Bench Division – This division deals mainly with common law cases concerning contract and tort.

b. Chancery Division – This division deals with the more complex, specialist areas of civil law, such as property disputes, business matters, probate, intellectual property etc.

c. Family Division – This division deals with appeals from the Family Court and it has exclusive jurisdiction over certain matters such as wardship proceedings.

5. The Divisional Courts of the High Court

At first glance, this seems confusing as the High Court is already split into divisions, but the Divisional Court is an entirely separate court as it is the appellate court (or court of appeal) for the High Court. Each of the High Court divisions described above has its own respective Divisional Court.

Criminal Courts

Magistrates’ Court

All criminal cases start life in the Magistrates’ Court, even the most serious offences such as murder. Criminal offences are categorised as summary only (can only be dealt with at the Magistrates’ court) or either way (can be dealt with at either Magistrates’ or Crown Court) or indictable only (can only be dealt with at the Crown Court). For example, a speeding offence is summary only, a burglary is either way, and murder is indictable only.

With either way offences, the magistrates’ court will have to decide whether the offence is so serious and/or complex that it cannot deal with it and it ought to be sent to the Crown Court. This may be because of the issues involved, or perhaps because the anticipated sentence in the event of a conviction far exceeds the Magistrates’ sentencing powers.

Indictable only offences (such as murder) must start at the Magistrates’ Court where they are formally sent directly to the Crown Court, without even the opportunity for the defendant to enter a plea. You can find out more about Magistrates here.

Youth Court

The Youth Court hears criminal cases involving juveniles (aged 10-17), even on very serious charges that had the person been an adult, would have been dealt with in the Crown Court. In addition to reduced levels of formality, Youth Courts have very different sentencing powers to adult courts.

Crown Court

The Crown Court deals with criminal trials, criminal appeals from the magistrates’ court and some civil appeals. It, therefore, has dual jurisdiction as a court of first instance and as an appellate court. In relation to criminal matters, the offences that are indictable only, or either-way offences that have been deemed too serious for the magistrates’ court, will be tried at the Crown Court.The three different classes of offence dealt with are:

-

- Class 1 offences – the most serious offences (e.g. murder), generally heard by a High Court judge.

- Class 2 offences – very serious offences (e.g. rape), generally heard by a circuit judge.

- Class 3 offence – everything else, heard by either a circuit judge or a recorder.